Reflective practice

Professional educators seek to improve their skills and competencies systematically. They notice things about their teaching that they would like to improve, address one or two items on that list for development, and, once resolved, move onto another. They analyze both their practice and gaps in their knowledge as they go along, thinking consciously about what happens in their classrooms, and look to improve continually. Those needs and improvements may come from reading, action research, peer observation, observation or student feedback, or other sources, such as training sessions, but they must involve both input and experimentation in the classroom. This systematization of Professional Development (PD) is the essence of Reflective Practice: simply put, trying new things and accepting or rejecting them.

However useful training may be, it is often too random for the individualized development - primarily focused on input or workshops identified for a large faculty or determined by system needs: in other words, it may be useful to you, but if organized by institutions does not purposefully address your particular needs as a teacher: you may find useful ideas, but perhaps only by coincidence. Furthermore, there is not usually a formal requirement to try these practices out in your classes. To bridge the gap between theoretical input and classroom output, then, and to assist in your development as a Reflective Practitioner, we are asking you to keep track of personalized Action Points (APs) and integrate them into your classroom teaching during the year - a nudge to try out new ideas in response to gaps you've noticed yourself.

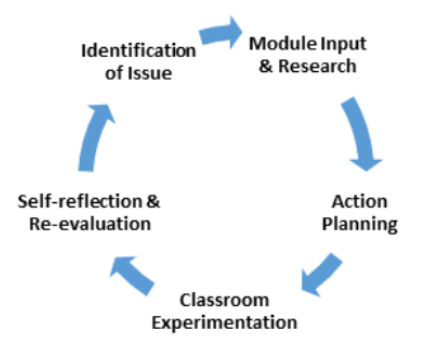

This document thus creates a virtue circle that links input to output, and to reflection, in a cycle that generates ongoing improvements in your teaching, as represented below:

PHASES OF REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

Reflective practices should be divided into two main phases.

|

Phase One: Reflections on Your Teaching - What You Want to Develop

First, identify an issue that you want to resolve. It may help to think of answers for these questions:

Example One – here is an example of an idea which is not very helpful: ‘I don't feel confident when teaching online.’ Example Two – here is an example of an idea expressed more concretely: ‘I want to learn how to keep more learners engaged in online interactions. I've noticed that it's difficult to keep large groups of students contributing meaningfully when teaching online. This makes me uncomfortable, because I feel as though I'm not doing my job very well, but I also worry about their grades and lack of progress if it continues. This will have negative consequences for them and for me!’

|

|

Phase Two: Action Planning

In this phase, you will: record what specifically you want to try out to resolve your issue, and with which class;

Example One – here is an example of an AP that is below the expected standard: ‘I will start recycling vocabulary more often.’ Example Two – here is an example of an AP that would be more helpful: ‘I will use ‘Backs to the Board’ with my Stage 4 class to make recycling vocabulary more engaging and communicative, and to gauge the learners' accuracy of oral production of targeted lexis from the previous phase or lesson. For me, this is useful because I do not recycle vocabulary very often and often don't know how well the students can reproduce what was learnt in a prior lesson, in terms of accuracy of meaning or pronunciation. This doesn't usually come out with dry matching activities or gap fills that I set as checks for homework. This game gives students a chance to describe the lexis and listen to each other in a fun game, so it integrates oral skills with the language review.’ |

|

Phase 3: Evaluation

Example One – these are reviews of an AP that do not assist understanding: ‘When I tried the game, it got very noisy. I don't know if was useful or not.’ 'The game was really good and did exactly what I needed. I'll use it again!' Example Two – here is a review that better exemplifies a higher standard of reflection: ‘I used ‘Backs to the Board’ with my Stage 4 class last Monday - a fun way to start the week and review previous lexis. It got very noisy with several teams shouting at once. This made it hard to identify who knew the vocabulary and who didn't. It was definitely communicative, and everyone enjoyed it - lots of oral production and a fun way into reviewing target lexis. However, I need to find a way to differentiate a bit more, so that the stronger students aren't dominating and shouting loudest. This could be done by grouping learners differently, giving clue cards to less able students, or getting teams to take turns - with easier words for the less advanced to describe. Nevertheless, I will definitely use it again, because there was a lot of speaking - I just need to guide the production better.’ Once you have evaluated this attempt to resolve one of your issues, reflect on whether you are satisfied with the result. Ask yourself these questions to help:

If the answer to such questions is 'not yet', then you may want to source another potential solution and try again to resolve the issue at hand. If the answer is 'yes', though, then you can move on to think of another you want to resolve. The practice is therefore cyclical and continuing. |

SAMPLE OF REFLECTIVE JOURNAL

Teachers are not required to use any compulsory template for their reflective journal and development plan. Below are two among various samples that have been used at Vinschool for your reference.

- Reflective Professional Development Action Plan template (which to be made throughout the school year, after each lesson, each unit or a particular instructional phase)

- Individual Development Plan (IDP) (which to be made at the beginning of the school year and reviewed periodically by teachers and heads of departments)